An Ecology of Happiness

Happiness across the four modes

Nov 16, 2025

By: Michiel Knoppert

What if our struggle with happiness is not that we don’t have enough of it—but that we’re conditioned to chase only one kind?

This article is part of a broader exploration of the Uncivilize framework, which proposes four modes of human living (Global, Local, Domestic, and Wild) that help us understand how we live our modern lives is a choice, that different paths are open to us to transition towards lives that are happier, healthier, more humane, and more sustainable. To understand these modes—and how they can help guide change—we need to understand something equally fundamental: the nature of happiness itself.

We tend to treat happiness as a single thing, a state we're supposed to pursue, something we could earn, buy, or unlock, but psychology, philosophy, indigenous wisdom—even evolutionary theory—all point to the same insight: happiness is not one thing. It is a gradient.

There is a spectrum from shallow, external, fleeting happiness

to deep, internal, lasting happiness.

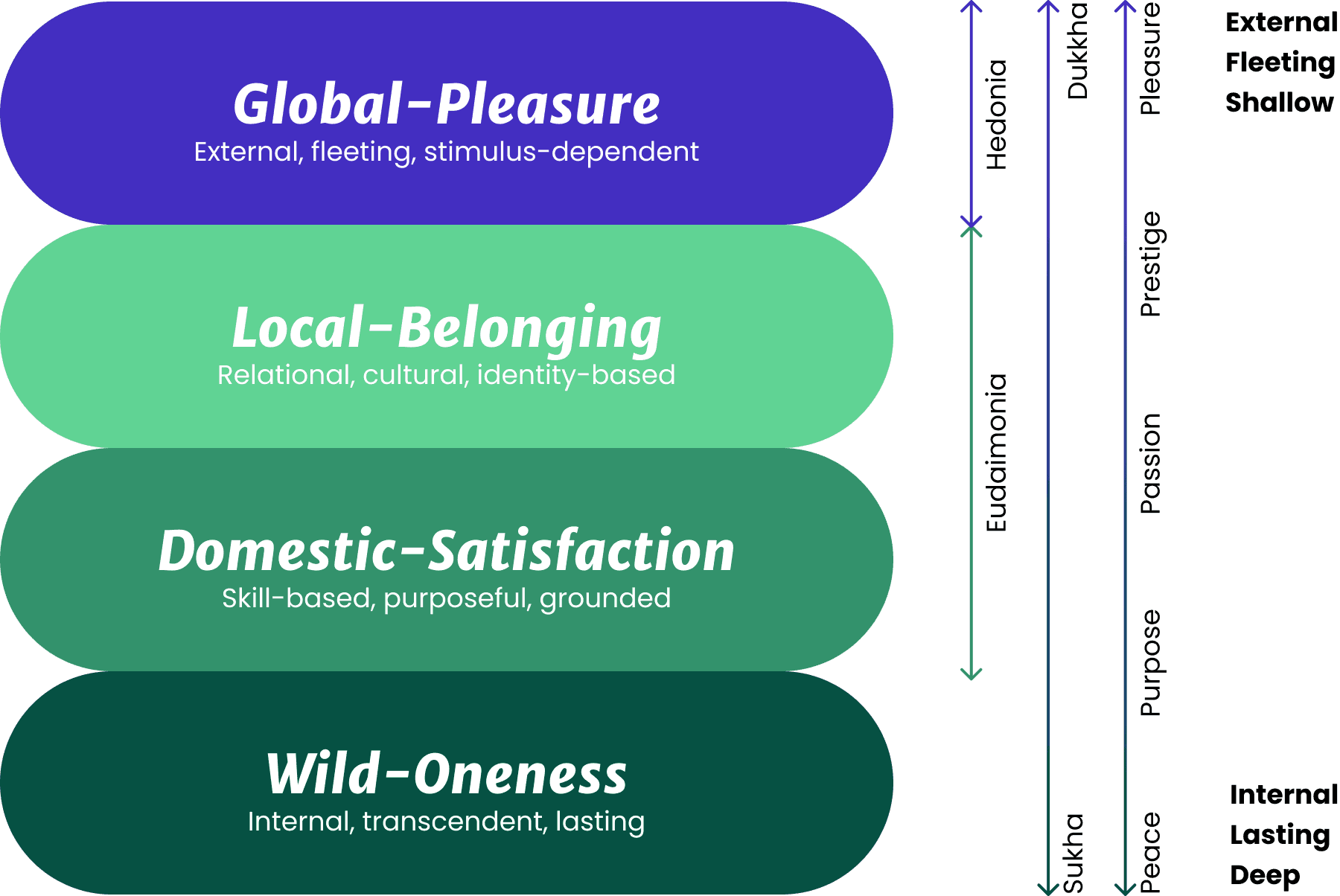

In Eco-Liberalism, Kees Klomp captures this beautifully with his spectrum running from happiness that is completely dependent on external factors, to happiness that comes from within; pleasure-prestige-passion-purpose-peace. His layering echoes other concepts like: Hedonia and Eudaimonia and Buddhist teachings on Dukkha—suffering from craving and attachment fueled by materialism—and Sukha—a state of comfort, pleasure, wellness, and well-being. What is even more striking is how naturally this spectrum lines up with the Uncivilize modes. It is not that each mode offers only one kind of happiness; rather, each mode is especially fertile soil for certain kinds of happiness.

By balancing all modes we create a diverse landscape of ways to feel alive and flourish. This article explores how each mode is conducive to different kinds of happiness, why modern life has collapsed this spectrum into a narrow unfulfilling pursuit of happiness, and what we need to restore a fuller, more grounded experience of happiness.

Global Mode — Pleasure

External, fleeting, stimulus-dependent.

Global mode is the breeding ground for external happiness. It excels at producing pleasure and status—the fast, bright, high-stimulation end of the happiness spectrum. This is the realm of convenience, consumption, competition, and the dopamine-on-demand economy. It gives us peaks: the quick delight of buying something new, the rush of achievement, the stimulation of endless entertainment. These forms of happiness are quick bursts, measurable, marketable—and fundamentally fragile. They fade quickly, require constant input, and depend entirely on forces outside ourselves. Psychology has been remarkably consistent about their limits: hedonic pleasure and external validation cannot sustain a flourishing life. From a Buddhist perspective, this mode is also the most vulnerable to dukkha, the subtle dissatisfaction that comes from chasing impermanent rewards. The Global mode is rich in stimulation but thin in depth.

Local Mode — The Happiness of Belonging

Relational, communal, identity-based.

In Local mode wellbeing changes texture. Happiness is no longer about pleasure but about belonging—the comfort of being known, the grounding of place, the security of being needed. But Local mode also opens the space for something deeper: self-actualization through relationship, you don’t just belong, you become. You discover who you are by discovering the role you play in a community—what you contribute, what others rely on you for, how your talents fit into a shared whole. Local life produces the kinds of happiness that frameworks like PERMA call relationships and meaning, and that Self-Determination Theory identifies as relatedness. You matter because you participate. Your identity is braided through people, place, and culture. You see it in neighborhood initiatives, in collective projects with shared purpose, in forms of specialization that are practical rather than abstract—a stark contrast to the “bullshit jobs” that emerge from remote, bureaucratic global systems. In Local mode you are recognized, not as a consumer or a cog, but as a person with a place. It creates a durable form of happiness grounded in cooperation, appreciation, and shared identity.

Domestic Mode — The Happiness of Satisfaction

Skill-based, purposeful, grounded.

In Domestic mode, where you care directly for your inner circle, a different form of wellbeing becomes abundant. This is the domain of practical knowledge and skill, one of our deepest psychological needs. When you cook, repair, build, grow, tend, or create, you tap into Eudaimonic wellbeing: satisfaction rather than stimulation; accomplishment rather than achievement. Craft and care invite sustained focus, subtle challenge, and immediate feedback, making them fertile ground for flow. While this mode does not offer the sharp spikes of pleasure that the Global mode specializes in, it offers something steadier: the grounded contentment of being useful, capable, and connected to the material world. A Buddhist might see this as a form of meditative absorption, the calming of the restless self through present, intentional action. Here, happiness grows through practice, patience, and the quiet pride of becoming better at something that matters.

Wild Mode — The Happiness of Oneness

Internal, transcendent, lasting.

And then there is the Wild mode—the deepest layer of wellbeing, and the one modern society has most forgotten how to access. This mode does not produce pleasure or status. It produces peace, unity, awe, and the softening of the boundaries of self. You feel it when walking in a silent forest, when mountains dwarf your worries, when the ocean pulls you into its rhythm, when psychedelics loosen the grip of the ego, when you become again part of the living world. Psychology calls this self-transcendence; indigenous cultures consider it simply being human; Buddhism understands it as the relief that comes when grasping quiets. This is not happiness as pleasure but something more profound: a sense that life is coherent, connected, and alive.

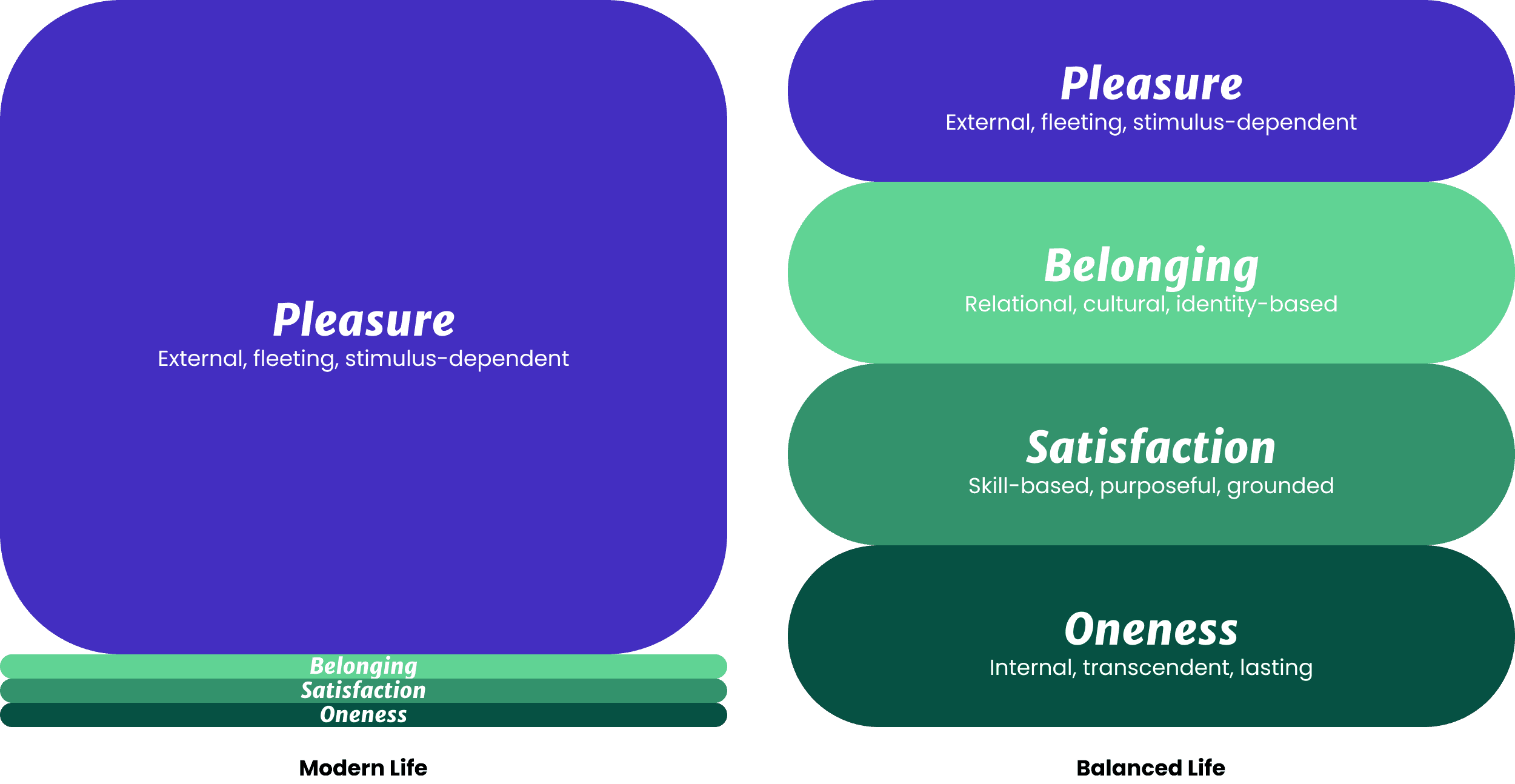

Why We Suffer: A Monoculture of Happiness

What becomes clear across these modes is that pleasure can be bought, but true wellbeing and lasting happiness emerges more easily from the modes that modern life pushes aside. Global mode gives us external peaks of short-lived pleasure. Local mode gives us belonging and purpose. Domestic mode gives us mastery and satisfaction. Wild mode gives us peace and oneness. Each mode activates different human needs—pleasure, competence, relatedness, meaning, transcendence. Across psychology, philosophy, anthropology, and Buddhist thought, the conclusion is the same: a monoculture of wellbeing leaves us deprived.

We suffer today not because happiness is scarce, but because we’ve narrowed it to what industry can mass-produce. Our lives are rich in stimulation but poor in meaning; rich in convenience but poor in mastery; rich in entertainment but poor in peace.

A Fuller Life

If we want fuller lives, we don’t need to chase more happiness—we need to diversify the modes we inhabit. We need to restore the full ecology of wellbeing. Only then does happiness stop being something to pursue in vain, and become something lasting that grows naturally from the way we live.