Uncivilizing Design

Beyond Industry, Back Into Life

Nov 21, 2025

By: Michiel Knoppert

The Capture of Design by Global Mode

Modern “industrial” design—firmly rooted in what we call Global Mode—is structurally entangled with the systems driving today’s polycrisis. What was once a craft concerned with shaping useful, meaningful objects has become an engine for commercial expansion, shareholder value, constant refresh cycles, and the manufacture of desire. It optimizes products for mass manufacture through global, energy-intensive supply chains, leaning heavily on specialized technologies whose complexity locks us into dependence. This is the world of amazing materials, magical electronics, and logistics systems operating at planetary scale. These techniques enable mass production, but they also generate enormous waste, demand staggering energy inputs, rely on extraction and exploitation, and make repair nearly impossible—thus accelerating product churn and shortening lifespans by design.

Victor Papanek warned of this trajectory half a century ago when he argued that design had been diverted into triviality, producing “junk jobs for junk products” instead of serving real human needs. Ivan Illich identified the parallel pathology in tools and systems: once they exceed a certain scale and complexity, they cease to be liberating and instead become “radical monopolies” that crowd out simpler, more convivial alternatives. Global Mode design, taken as the default context for all design thinking, exemplifies the radical monopoly. It narrows the imagination until only industrial-scale solutions seem legitimate.

Designers, shaped by industrial education, are trained to imagine solutions within this system. The imagination becomes industrialized; the boundaries of possibility tighten around whatever fits the global production funnel. It becomes difficult—even conceptually—to picture what a product might look like if it were designed for local workshops, for household fabrication, or in partnership with nature.

Liberating the Designer’s Skillset

Uncivilize does not reject the designer’s abilities. It rejects the industrial system that has captured those abilities and redirected them toward extractive ends. Most of the skills cultivated through design education remain invaluable: sensitivity to form and proportion, an eye for aesthetics, mastery of visualization, clarity in storytelling, deep knowledge of materials, the ability to choreograph user experiences, and—most critically—problem-solving and systems thinking. Designers understand how parts fit together, how interactions unfold, and how objects shape behavior.

Papanek argued that these abilities were being squandered on “gadgetry” and marketing, but he also believed that designers could be powerful agents of social good if freed from commercial imperatives. Illich would add that designers should help create convivial tools—tools that expand human agency rather than replacing it or enclosing it within expert-only systems. Uncivilize builds directly on both insights: the designer’s potential becomes fully visible only when it is decoupled from the industrial machine it currently serves.

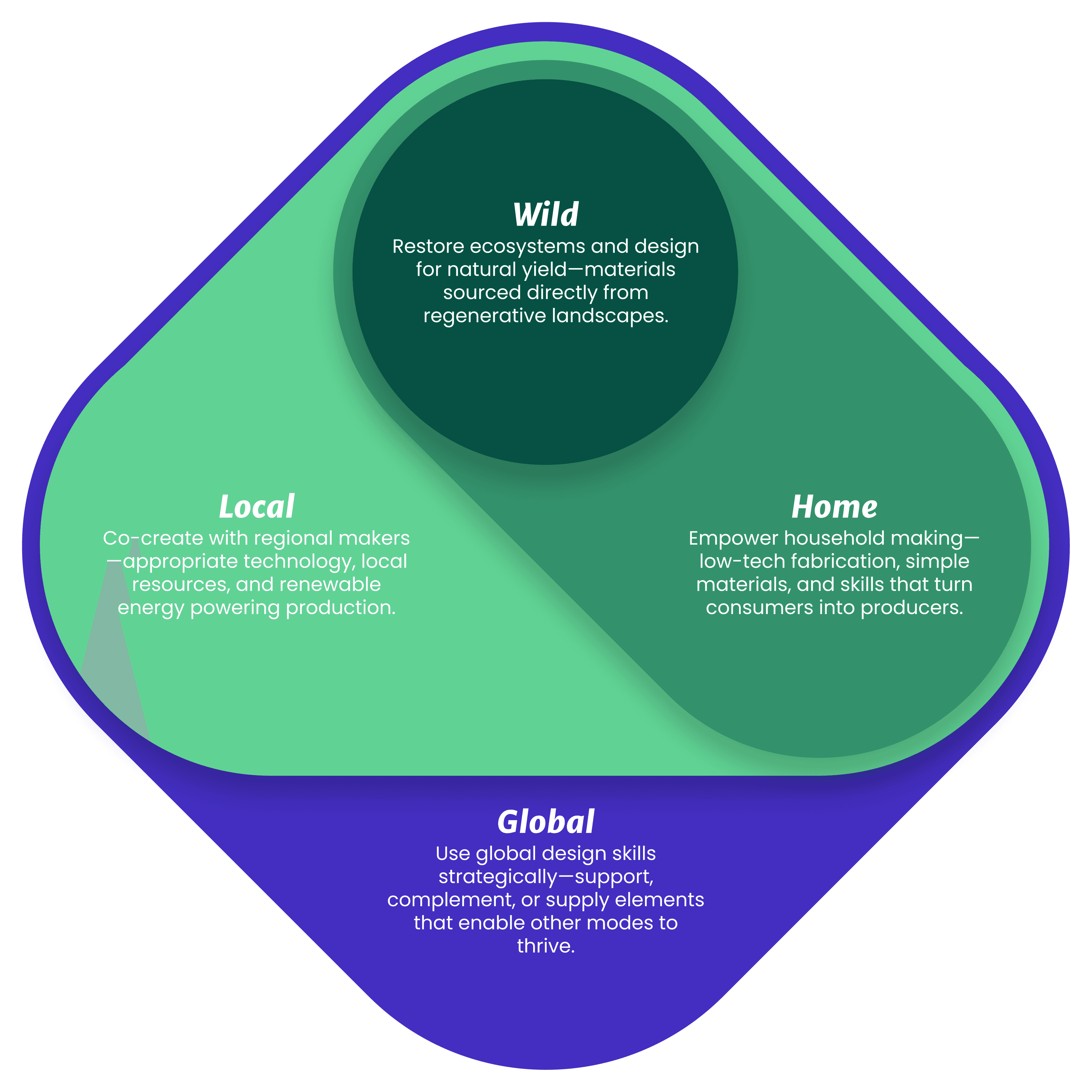

From Industrial Producer to Cross-Mode Orchestrator

In the Uncivilize framework, the designer’s role shifts profoundly. Instead of producing for global industry, the designer becomes an orchestrator—someone who operates across multiple modes of production. They mediate between Wild Mode, where materials are sourced through regenerative relationships with ecosystems; Domestic Mode, where households make and maintain low-tech solutions with common tools; Local Mode, where regional industry uses appropriate technology to fabricate durable, repairable goods; and Global Mode, which remains present but no longer dominates—serving instead as a coordinating, visualizing, and propagating layer.

This shift begins with a new question: Which mode is the appropriate home for this solution?

Instead of defaulting to industrial manufacture, the designer intentionally positions each solution where it can thrive with the least ecological burden and greatest social benefit. This reorientation echoes Illich’s insistence that communities should choose the scale and technological threshold that empowers them most, and Papanek’s call for designers to address real needs with appropriate means.

Recalibrating Expectations Through Design Sensibility

People living in industrialized societies are conditioned by the visual and functional polish of commercial products. They expect precision, cohesiveness, and refined aesthetics shaped by decades of industrial design language. Local craft and household production don’t match these expectations—not because craftspeople lack ability, but because industrial design has defined the aesthetic norm.

The designer therefore plays a crucial role in translation: carrying forward the dignity, clarity, visual coherence, and usability that industrial design cultivated, and expressing them through the grammar of local materials, domestic toolsets, and low-tech processes. Instead of designing for injection molding or automated assembly, the designer works with timber from the region, reused metals, simple joinery, solar-heated processes, and tools accessible to households or village workshops.

This shift naturally increases quality, lifespan, repairability, and human-scale engagement—values that Illich saw as essential to convivial societies, and which Papanek championed as the antidote to disposable culture.

Making Alternatives Visible and Credible

Designers play an essential role as sense-makers. They give shape and legitimacy to local, domestic, or wild-mode solutions that otherwise remain abstract or invisible. They create prototypes, diagrams, stories, and visual demonstrations that help policymakers, funders, community groups, and citizens see non-industrial futures as viable. What industrial designers once did for corporations—making the future tangible—they can now do for local resilience and ecological integrity.

Papanek famously noted that “the only important thing about design is how it relates to people.” In Uncivilize, visualization becomes a way of relating to communities and enabling them to see themselves as capable makers, not passive consumers.

Designing Blueprints, Not Specifications

Industrial design produces rigid, highly specified artifacts: CAD files dictating every tolerance and process. Uncivilize design produces adaptable blueprints—frameworks that local craftspeople or domestic makers can interpret using the tools and materials available to them. The design becomes context-aware. It expects variation. It invites reinterpretation.

This reflects Illich’s vision of convivial tools: systems designed for flexibility, modifiability, and user agency, rather than precision-engineered dependence. For Papanek, such an approach would have been the ultimate redemption of design—a return to serving real human needs with humility and intelligence.

Design as a Distributed, Locally Productive, Globally Connected Practice

Reclaiming design as a shared human activity means acknowledging what industrialization displaced. For most of human history, people designed and made much of what they needed themselves. Design was woven into daily life—an ordinary form of creativity and problem-solving. The rise of Global Mode professionalized and centralized the discipline. Designers were absorbed into corporate structures, and citizens became consumers, their creative agency reduced to “DIY projects” supported by shelves of pre-selected kits.

The Uncivilize framework aims to reverse that drift. It restores design as something that circulates through households, communities, and regions—not only within institutions. This echoes Ezio Manzini’s vision of “distributed, locally productive, globally connected systems,” where design expertise is no longer locked inside the industrial apparatus but shared, taught, and adapted across contexts. Designers don’t disappear; instead, they expand their role by cultivating local capability.

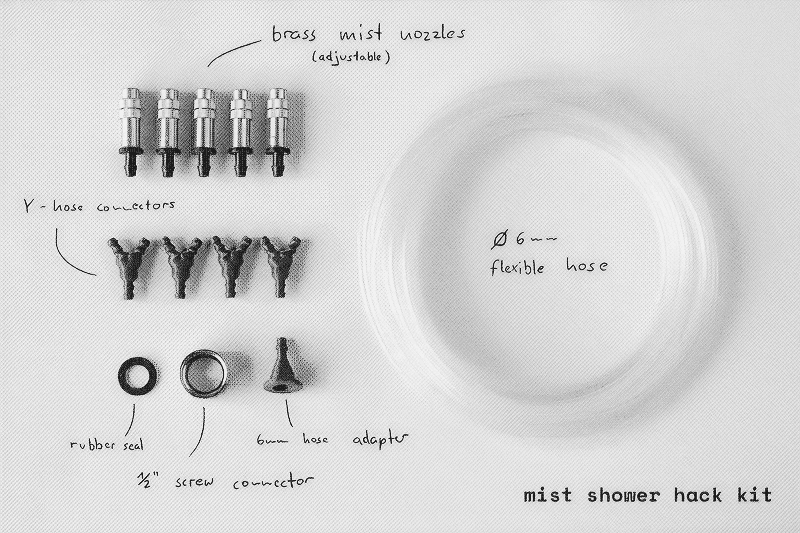

Work like Kris De Decker’s Low-Tech Magazine shows what this looks like in practice: solar cookers, mist showers, human powered machines. These are not consumer products but open invitations—blueprints meant to be built, modified, and improved by whoever needs them. They demonstrate how global knowledge can support local autonomy.

image: Mist Showers: Sustainable Decadence? courtesy of Kris De Decker

Propagation Instead of Mass Manufacture

Instead of global corporations distributing millions of products, the spread of ideas becomes the work of designers (or the outfit they're part of), they enable millions of people to create it themselves. Propagation replaces mass production. Designers release plans, run workshops, create documentation, develop open hardware, and produce kits that complement what users can make themselves. Income may come from blueprint sales, teaching, community fabrication, or small-scale product runs.

The design becomes seed material—a generative starting point that communities adapt, extend, and care for. This is precisely the kind of decentralized, community-sustained innovation Illich believed would restore autonomy and diminish radical monopolies.

Reconsidering Where Things Should Be Made

Choosing the mode of production becomes a central design decision. If Local Mode is viable, it becomes a powerful choice. Local Mode does not mean quaint hobbies—it includes serious regional manufacturing: workshops capable of producing wind turbines, water systems, stoves, pumps, solar-thermal heaters, and mechanical infrastructure using appropriate tech and renewable energy. Domestic Mode allows households to shift from consumer to producer through low-tech, repairable fabrication. And if a product can be sourced directly from nature, Wild Mode asks designers to think ecologically: harvesting in ways that restore ecosystems, not deplete them.

This is design aligned with Papanek’s moral imperative and Illich’s technological threshold—solutions sized to human and ecological scale.

Production in Each Mode and the Designer’s Role

Local Mode: Co-Creation With Regional Makers

If an idea can be executed with appropriate technology, using local or regional manufacturers powered by renewable energy and relying on regionally grown materials or urban-mined waste streams, then it naturally belongs in Local Mode. Here, the designer develops a blueprint grounded in these criteria from the very beginning. The blueprint is not a fixed mandate—it is an invitation to collaborate. It is shared with local craftspeople, workshops, and regional manufacturers who adapt it based on the tools, skills, materials, and traditions actually available in their area.

Local culture, climate, and craft matter. The designer works directly with these producers to arrive at a solution that is technically feasible, economically workable, and culturally meaningful. Income comes from involvement in the implementation process—from design fees to royalties, to payment in kind, depending on the relationship with the local makers. The designer is not distant; he is embedded in the regional ecosystem of knowledge and production.

Let's use laundry as an example. A local mode solution might offer community-scale laundry spaces powered by wind and solar-thermal systems. Run by local co-ops, made by local industry with materials from the bio-region including salvaged waste materials.

Domestic Mode: Downshifting Production Into the Home

When an idea can be executed with low-tech tools and common knowledge—through cottage-industry methods, household workshops, or homecraft—it makes sense to shift production into Domestic Mode. This brings making closer to the eventual user: people become producers again, capable of fabricating, repairing, and caring for the things they rely on because they understand how these objects work.

Even if the manufacturing can also be scaled up to Local Mode, the deliberate choice to downshift materials and technology lowers impact and improves autarchy. Because there are now too many dispersed producers for the designer to work with on an individual basis, the designer resorts to: selling blueprints, kits, workshops, tutorials, and instructions. In a world where practical making skills have largely been forgotten, this knowledge becomes a valuable service in itself.

Solutions for washing clothes in domestic mode are human powered and easy to use and maintain —they could even be produced at home— like scrub boards and plunger-style agitators, racks and lines for drying, and homemade soap made from simple ingredients.

Wild Mode: Designing for Ecosystem Yield

Wild Mode is the most radical and the most ancient. If a product can be simplified to the point where it can be harvested directly from nature, then that is where the design work must go. Here, the designer’s role shifts from shaping objects to shaping relationships between humans and ecosystems.

The work becomes ecological: restoring habitats, regenerating degraded land, reintroducing species, stabilizing watersheds, and designing ways for people to steward landscapes so that they produce a sustainable yield of materials—fibers, woods, resins, clays, foods—while simultaneously strengthening ecosystem services and climate resilience. These materials may then flow into Domestic or Local production, creating a living bridge between modes.

In Wild Mode, families can grow or forage saponin-rich plants like soapwort and soap-nuts, or produce lye from wood ash as detergent and use a nice flat rock in a local water stream for washing, while spreading the laundry out in a field of grass allows them to dry in the sun.

Global Mode: From production to support.

A regular global mode solution would offer a smart, modern, automated experience that offers —above anything else— convenience. The designer embraces global supply chains and every available technology to create something appealing that offers efficiency and convenience while keeping production costs low. From disposable —easy dosing— packaging of petrochemical detergents, to energy-heavy, complex, internet-connected machines for washing and drying, and —for early adopters— robots to take over the remaining manual work of loading and folding.

Within the Uncivilize Framework, the designer’s role in Global Mode changes fundamentally. We do not expect industrial production to disappear; it will continue where it makes sense, and millions of designers will continue working within it. But because this domain already receives massive attention, talent, and investment—and because its primary challenge is to become less harmful rather than fundamentally different—there is no need to center it in this framework.

Instead, the Uncivilize designer uses skills acquired in industrial design—systems thinking, material literacy, prototyping, ergonomics—to support transitions into Local, Domestic, and Wild Modes. Global Mode remains available as a source of components or materials when truly necessary (the LED, the internet, the microcontroller), but production itself is relocated to the modes that better reflect human and ecological limits.

Now we can move toward the deeper question of how these modes braid together, forming hybrid solutions that benefit from the strengths of each.

Braiding Solutions Across the Modes

Some of the most powerful, visionary designs do not belong to a single mode—they braid them. In this braided space, a single system or object can draw on materials from Wild Mode, be pre-processed in Domestic Mode, assembled in Local Mode, and shared globally through Global Mode blueprints and community networks. The designer, as orchestrator, holds the vision of quality and coherence but must also think on their feet: they must anticipate constraints, adapt to unforeseen local material shortages, collaborate with makers, and negotiate trade-offs in real time.

This requires a very particular kind of designer: one who is curious, humble, flexible, and deeply attuned to ecological, technical, and social realities. They don’t just issue a final drawing. They engage with the communities that build, maintain, and repair. They help solve problems that emerge when a blueprint meets a village workshop, or when a foraged material must be cleaned or processed. They nurture relationships; they mentor makers; they learn by doing.

In doing so, they preserve the integrity of design quality—not as industrial polish, but as thoughtful, adaptable, enduring form. They sustain a standard of care, while allowing local variation. And as they weave between modes, they knit together a new economy: one in which design is not a footsoldier of global growth, but a catalyst for ecological balance, social resilience, and meaningful production.

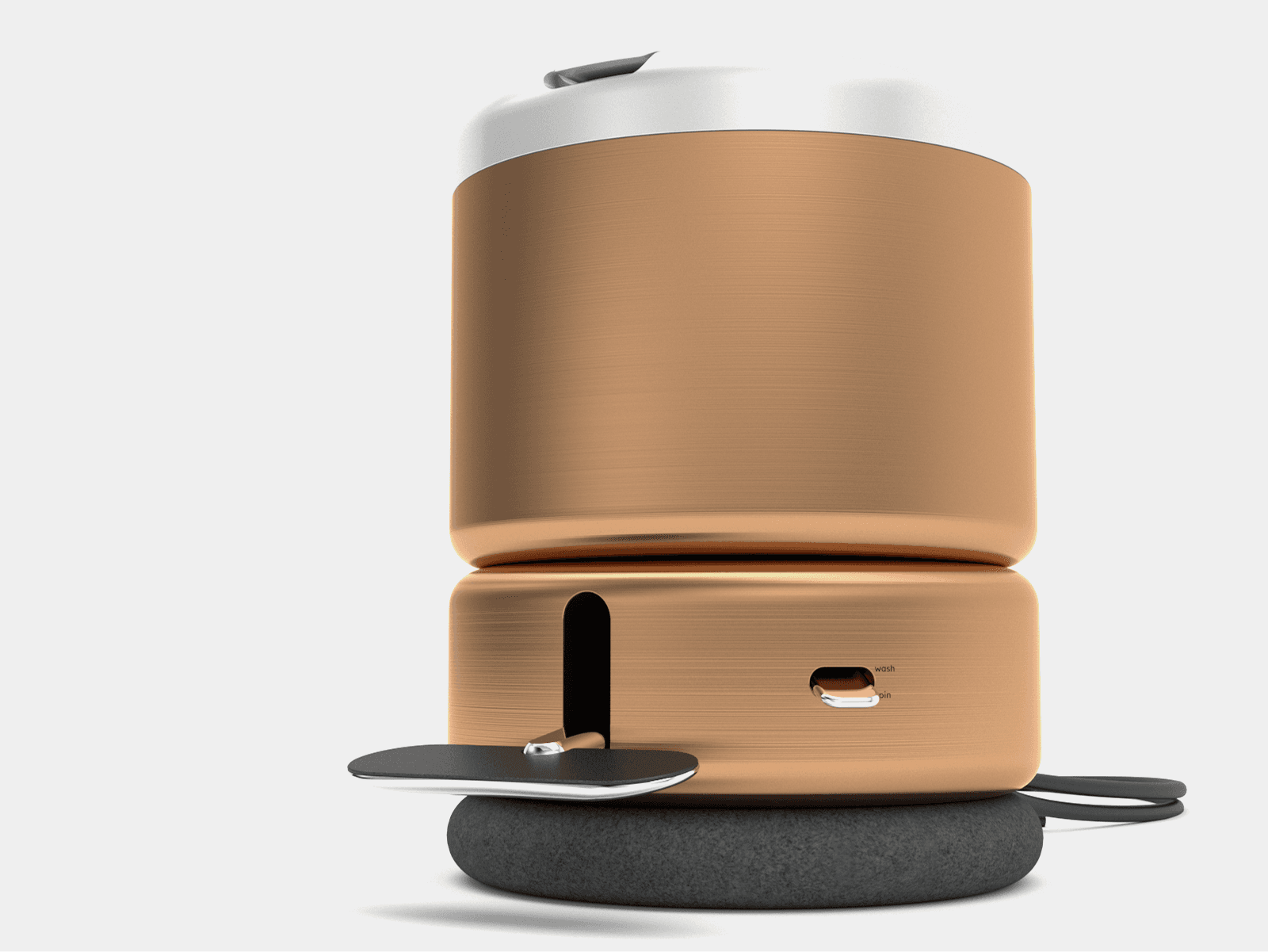

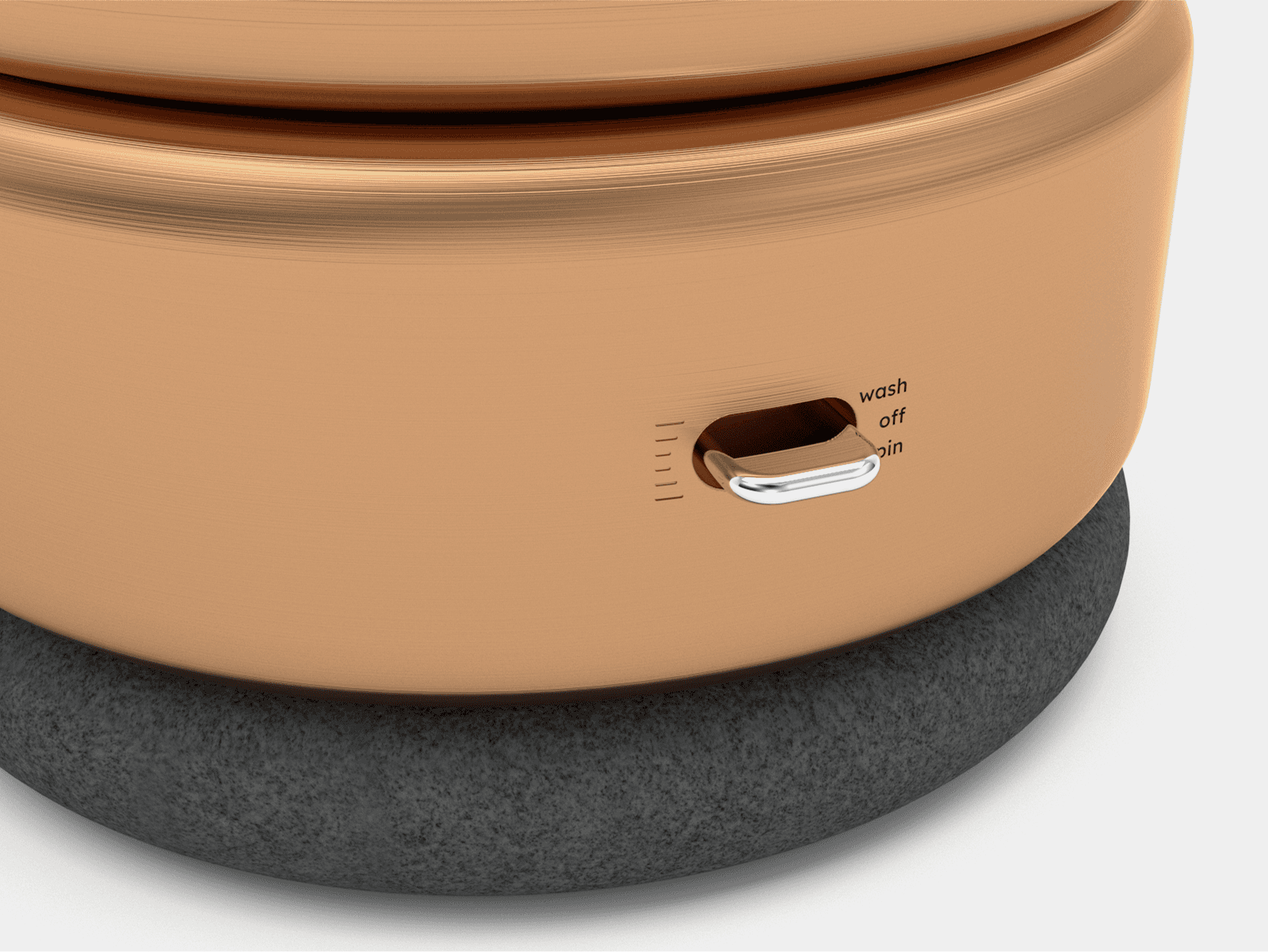

Back to our laundry example. The appliance begins with a designer’s blueprint but is built through regional manufacturing using locally available materials. Its drum is sourced from reclaimed washing machines.

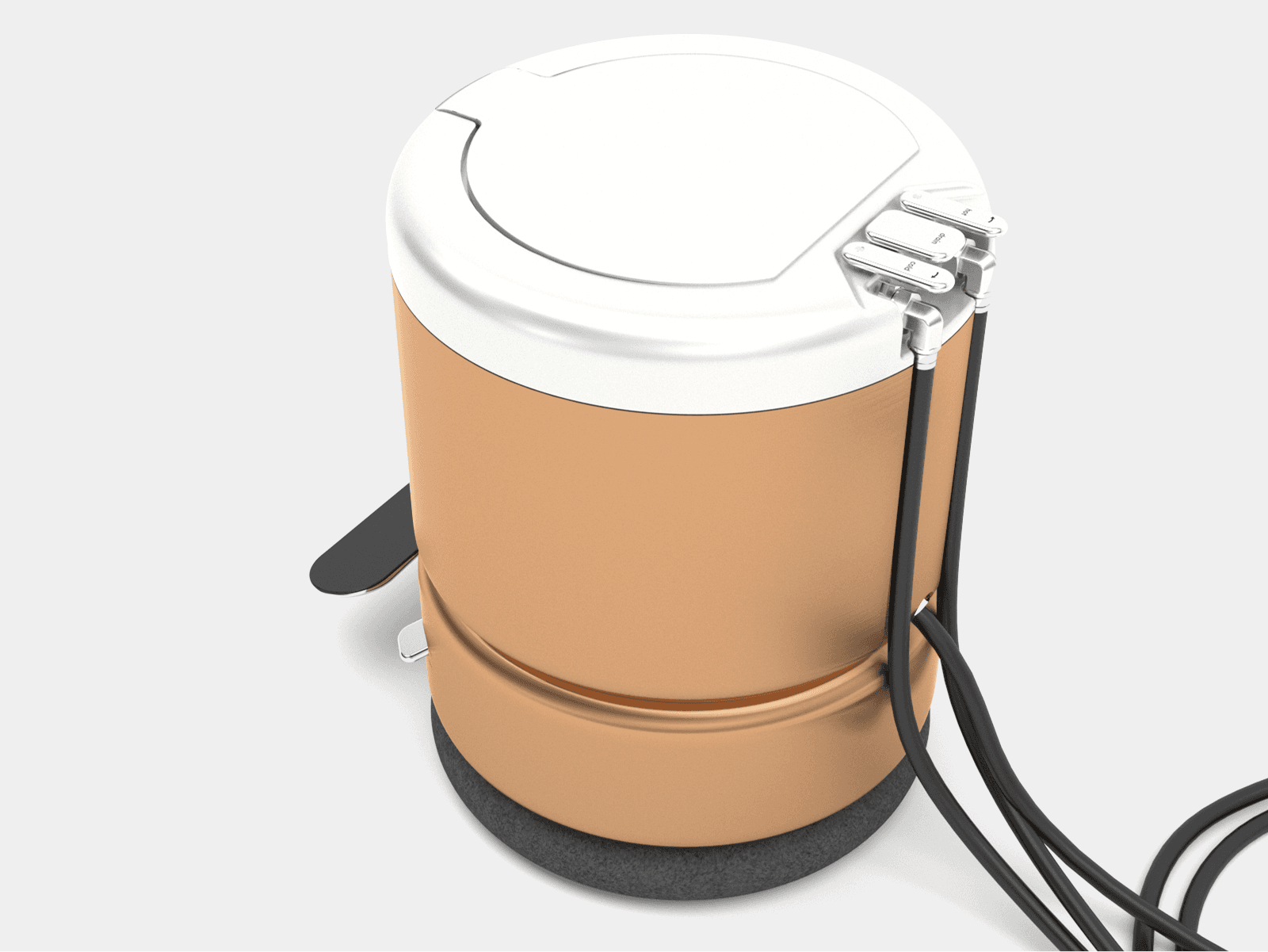

The device consists of three stackable modules.

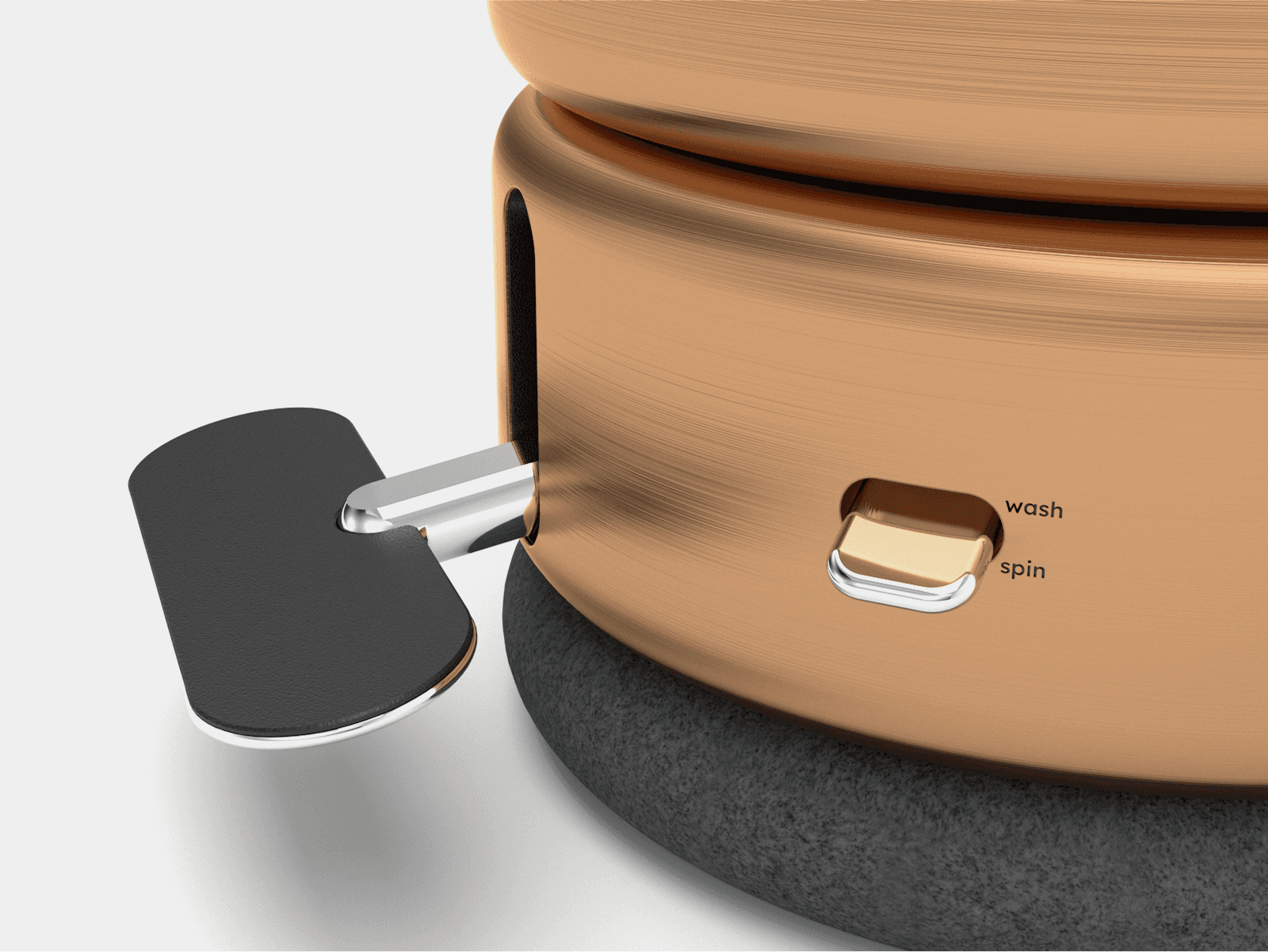

The base is a granite or concrete disc that provides weight and stability without relying on complex housings.

The drive module can be fitted with either a human-powered pedal system or a small electric motor that plugs into a battery or net-power.

The washer module simply pops onto the drive shaft, making repair, replacement, or upgrading straightforward.

Instead of disappearing into built-in cabinetry, the washer stands freely. You can approach it from any side, which greatly simplifies the design and serviceability but also allows it to be moved, to load it from the top and to sit on it while pedal-powering the cycle.

A top-loading drum keeps the design structurally simple and easy to fabricate locally. It also allows manual filling when the washer is not connected to plumbing. The tub accommodates hoses from tap water, rainwater tanks, gravity-fed systems, or solar-heated reservoirs—whatever the household or region provides and the outflow can either go into the garden or sewage system.

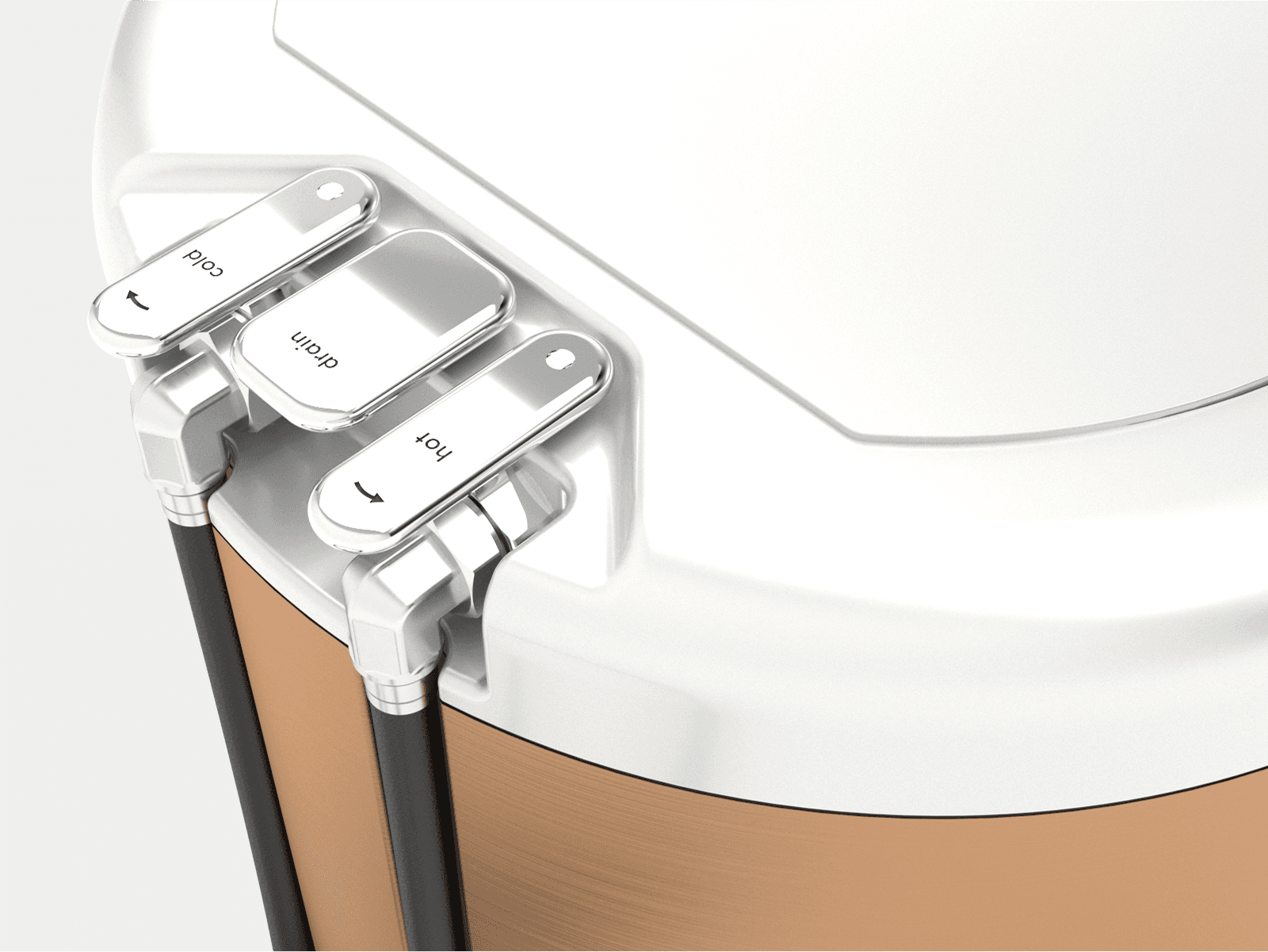

Two basic handles regulate warm and cold water if connected to taps. Temperature is adjusted by human judgment rather than a smart interface. Soap is dosed directly into the drum using experience rather than plastic cartridges, pods, or automated dispensers. Nothing is hidden behind electronics or proprietary systems; everything is knowable and adjustable by the user.

Operation is pared down to two modes: Wash and Spin. When pedaling, users naturally sense the required speed—just as they sense temperature or soap quantity. Switching to Spin engages a simple mechanical gear ratio that allows higher rotational speed for water extraction without additional electronics or fragile parts.

Soap options range from purchased detergents to homemade blends or natural, locally sourced ingredients. After washing, clothes are dried using a solar dryer or a simple line—closing the loop with low energy, minimal infrastructure, and maximum resilience.

Books & classic texts

Papanek, Victor (1971). Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change.

Illich, Ivan (1973). Tools for Conviviality.

Schumacher, E.F. (1973). Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered.

Mumford, Lewis (1961). The City in History (useful for technology & social organization).

E. F. (Ed.) — (you may cite other Schumacher essays/chapters if needed).

Design / sustainability theory & critique

Manzini, Ezio (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation.

Fletcher, K. (2010). Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys (or later edition).

Papanek, Victor (add any later editions/forewords as needed).

Economics / transition / degrowth (context)

Hickel, Jason (2019). Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (or essays/selected papers).

Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.

Circularity / policy reports (practical frameworks)

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (various reports; e.g., Towards the Circular Economy, annual reports).

European Right-to-Repair and Repair Café movement documents (cite local reports or summaries).

Permaculture / agroecology (wild & tended modes)

Mollison, Bill (1988). Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual.

Altieri, Miguel A. (1995). Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture (or reviews/meta-analyses).

Distributed manufacture / open hardware / makerspaces

Open Source Ecology — project documentation and the “Global Village Construction Set.”

Gershenfeld, Neil (2005). Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop — From Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication.

Literature on Fab Labs (MIT Fab Lab network documentation).

Repairability / social movements

iFixit — repair guides and advocacy (useful for Right-to-Repair examples).

Repair Café Foundation — movement descriptions, outcomes, and case studies.

Case studies & practical precedents (examples of distributed/local production)

Open Source Ecology case studies / documentation.

Selected co-op manufacturing examples (e.g., Mondragon summaries) and local renewable-energy workshops (regional reports or documented projects).

Method & metrics (to adopt in article)

ISO standards and LCAs — references to Life Cycle Assessment primer (e.g., ISO 14040).

Ellen MacArthur Foundation — material flow and circular metrics guidance.